This post was originally written as a paper in Paul Kockelman’s Anthropology of Information seminar.

What kind of scarcity can coexist with reproducibility? And how does it continue to serve as a source of value?

Here I’ll consider blockchain’s capacities as media, the nature of digital information, and the long existing social and epistemological practices that singularize and valorize objects as artworks. Doing so takes us through the information theory and cryptography of Claude Shannon and theories and histories of art by Walter Benjamin and Carlo Ginzburg. I show how NFTs employ blockchain as a second channel of artistic mediation in their use of cryptography. They develop a workaround to the problem of mechanical reproduction, allowing the artwork to circulate freely on the web while enclosing its metadata on the blockchain. To do so, and to derive value from this move, the technology adopts the concepts and procedures that have long animated the production and sale of art, namely presence and forensics. First, however, a technical introduction.

NFTs: An Anthropologist’s Primer[3]

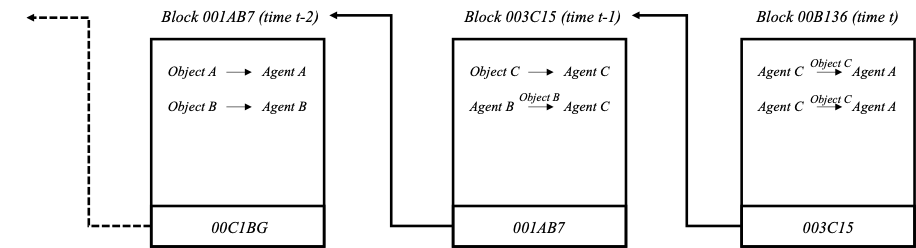

NFTs are applications of blockchain technology, a kind of cryptographically secured, distributed database system. Though whitepapers like Haber and Stornetta[4] presented initial visions of the technology in 1999, the design employed today largely draws from a 2009 whitepaper by Japanese computer scientist Satoshi Nakamoto.[5] As the technology’s name suggests, blockchains consist of individual blocks chained together. Blocks are timestamped containers for data, and each block records some kind of information—say a list of object-owner pairs or exchanges between two agents. This record is coupled with a pointer, or reference, to the previous block in the chain. Leveraging the timestamp, a single block represents the changes made to some state of affairs since the point in time represented by the preceding block. There are various kinds of blockchains currently in use, each with its own network of users who host copies of the chain on their local systems, and each with its own allowances for what kinds of information can be recorded in a block. A famous blockchain—and the first to reach widescale use—is the bitcoin blockchain, which records successive exchanges of bitcoin cryptocurrency, thus serving as a public ledger of the digital currency’s circulation. Another common blockchain is called Ethereum, which is currently the most popular blockchain for NFTs.

Figure: A simple blockchain schematic (by me)

A new Ethereum block is “mined,” so to speak, and appended to the chain with fresh data approximately once every twelve seconds.[6] “Mining” refers to the creation of a new block and entails the work of recording and securing all information collected by the system since the previous block’s creation. “Miners” are computers connected to the particular blockchain’s network (for example, the Ethereum network). Miners compete with one another to create a new block in exchange for a reward based in cryptocurrency.[7] Mining is no simple task because it involves a cryptographic hash function. A hash function is an algorithm that turns some input string of text, which can be of arbitrary and variable length (e.g., “Blockchain is complicated”), into an alphanumeric output string of a standard and fixed length (e.g., “1D7R089”). This output is called a hash. Hash functions are useful cryptographic tools for various reasons. First, hash functions are one-way in the sense that while it is easy to calculate the output given the inputs, it is impossible to perform the reverse calculation. (If A→B, it is easy to calculate B from A but impossible to calculate A from B). The only way to do so is to guess and check through trial and error. Second, hash outputs generally bear little resemblance to their corresponding inputs, and small changes in inputs typically produce widely different hash outputs. This makes guessing the input very difficult. Third, hash functions are deterministic in the sense that the same set of inputs will always produce the same set of outputs. This makes checking one’s guess easy and reliable; one can simply rerun the guess through the hash function and compare the outputs.

Mining entails the search for a hash. Miners are given a task by the system: provided a set of input data (in this case, the information recorded in the new block), append a number (called a “nonce”), thus tweaking the input data slightly. Then, run the hash function and check whether the resulting hash number satisfies some conventionally established criteria (e.g. the hash begins with two zeros like “00123”). When this fails, as it usually does, the miner tweaks the inputs again by appending a different nonce. It then reruns the function and checks the new result. This usually requires many guesses, and thus an enormous amount of energy, to produce a satisfactory hash number. Miners race to find a good hash, and once a potential winner emerges, the others check its work. This part is easy: with all the inputs now available, the others simply run the hash function and check the resulting hash number. This method is called “proof of work” and when completed, results in the addition of a new block in the chain with a corresponding hash number. The hash number then serves as the block’s identifier, and the next block in the chain will point to it.[8]

Blockchain uses hash numbers to secure the system from alteration and thus creates an inherently stable, “trustworthy” record.[9] The hash number allows for changes to be tracked; if a user in the system were to overwrite an old block’s contents by, for example, editing the details of a recorded exchange, the block’s contents would no longer correspond with its hash. (A→B, but A’↛B). This discrepancy would alert other members of the network of the change. Of course, the user could also overwrite the block’s hash number with one that matches the altered data. Since each block points to the previous block’s hash number, however, changing an old block’s hash number would break the chain, again alerting other members. Even if all the blocks were changed to preserve the chain of hash numbers, which would take an enormous amount of computing power, there are other copies of the chain in the system, and so a discrepancy would remain. This effectively makes a blockchain “append only” meaning that once a block has been added to the chain, it cannot be altered. As a result, the state of affairs represented by the chain can only be changed with the addition of a new block.

The blockchain provides the infrastructure for creating, storing, and circulating NFTs. “Minting” an NFT involves recording an object-owner pair in the latest block. As mentioned previously, the object itself, say a JPEG file, is generally not stored in the block. This is because it is usually too large. Instead, the object is stored elsewhere, for example on a separate server catalogued with conventional URL addresses. The blockchain only records the object’s metadata, which in its most basic form includes a unique identifier (e.g. the object’s name), its owner’s ID, and a pointer to the object (e.g. its URL).[10] Just as a block points to the previous block in the chain, then, so too does it point to all the external object files minted on it as NFTs. When an NFT is minted, the object-owner pair is recorded in a block, and after future exchanges, subsequent blocks can record the NFT’s transfers to news owners along with corresponding transfers of cryptocurrency in return. Given that NFTs contain metadata in place of the object file itself, however, blockchains do not provide a medium through which the object itself circulates during these exchanges. Instead, the object sits elsewhere.[11]

A Cryptographic Channel

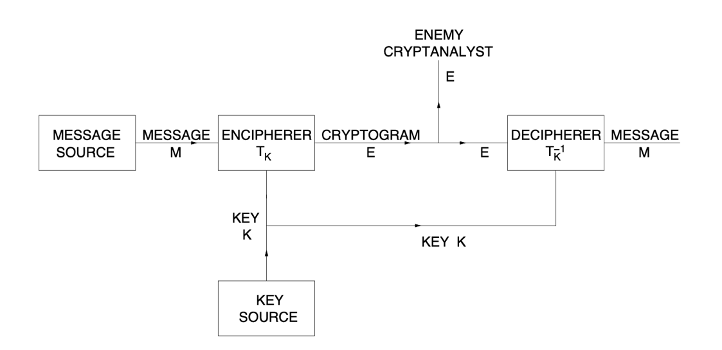

At the separation between art object and metadata, the copy/paste problem emerges. Critics claim that NFTs can be easily “stolen” because downloading and replicating an NFT artwork only requires the familiar and trivial right-click/copy/paste maneuver. Developers and proponents, however, argue that this misses the point—that scarcity can survive replication. Likening NFTs to long extant applications of cryptography can sort this out. The use of two channels, the secured blockchain and the unsecured internet—mirrors an approach introduced early in the development of cryptography: Claude Shannon’s secrecy system from 1949.[12] Shannon designed his secrecy system to conceal the meaning of an otherwise visible message. In this way, the system is different in purpose from blockchain, which as discussed was designed to record public information and protect it from unauthorized alteration. Nonetheless, both systems utilize two channels and leverage their combination of varying affordances. In Shannon’s system, pictured below, the first channel transmits the enciphered message, or the “clear,” referring to the ease at which it can be publicly accessed. This channel allows agents to efficiently transmit information, but as the diagram shows, it is also prone to an “enemy” seeking to intercept the message—what Serres would call a parasite in the network.[13] In Shannon’s account, radio is one such channel. The second channel transmits the key used to decipher the clear. It is more secure but less efficient, so while ideally the whole message could be transmitted through this channel, thus removing the need for encryption, doing so would be too costly, and thus only a small amount of information, the key—itself essentially a form of metadata—is transmitted this way. Already, the parallels may be clear.

Figure: Claude Shannon’s Secrecy System

Compare this with the two channels used by NFTs. The first channel is the Internet: the network of publicly accessible URL-addressed servers. This channel has long been open in the sense that information is easy to store and transmit. Yet this channel is not secure; on the Internet, messages can be intercepted, records can be altered, and information can be copied. The blockchain serves as the second, secure channel in this system. It provides a similar function as Shannon’s secure channel in the sense that while it is more costly to maintain—indeed, far more so—it allows for greater control over the mediation of information. Its proof of work protocol enables users to transmit and share metadata while securing it against unauthorized alteration. Interpreted through Shannon’s system, exchanging an NFT amounts to exchanging the key.

But how does metadata alone accrue exchange value when the art is still public and reproducible? Here it is worth revisiting Walter Benjamin’s classic essay on art in the age of mechanical reproduction.[14] According to Benjamin, art is traditionally distinguished as a singular, original object by its presence: “its unique existence at the place where it happens to be…the changes which it may have suffered in physical condition over the years as well as the various changes in its ownership” (220). What constitutes the experience of an artwork as a singular original—the aura—is precisely one’s encounter with this presence. For Benjamin, mechanical reproduction effects a “withering” of the aura because reproduction “substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence” (221). In other words, the presence is lost to replication. In this light, the copy/paste problem assumes such a withering of aura because it amounts to perhaps the most extreme form of mechanical reproduction achieved thus far. Not so fast, respond the NFT defenders: copy the piece all you want, but its metadata is now preserved and singularized on the blockchain. This secured channel attempts to neutralize the withering effect of mechanical reproduction, not by preventing reproduction outright, but rather by creating a separate, secured medium for the presence itself. In other words, the presence no longer resides in the artwork itself; rather it circulates as metadata on a blockchain

Benjamin celebrates mechanical reproduction’s withering of the aura for its transformation of artistic consumption and evaluation. Traditionally, he writes, “the unique value of the ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual, the location of its original use value” (223-224). He points to the historical use of art for magic and religious rituals. The ritualistic use of art has survived modern disenchantment and secularization, too, and he points to the secular “cult of beauty.” He calls this original use value art’s “cult value,” which depends not on the object’s visibility but rather its singular existence as an object available for ritual use. As an object of cult value, art can and has been hidden away.[15] On the other hand, “mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual” (224). The mechanically reproduced artwork derives value from its public circulation, and Benjamin accordingly calls this the artwork’s “exhibition value.” “Instead of being based on ritual,” concludes Benjamin, “[art] begins to be based on another practice—politics” (224). In other words, art circulates public discourse.

Benjamin’s account or reproduction may no longer hold in the case of NFTs. Again, the use of two channels is crucial. For Benjamin, the two kinds of artistic value, the cult value and the exhibition value, are mutually exclusive. This exclusivity only applies to systems with one channel, however. In Benjamin’s account, because the presence resides in the physical artwork, the artwork and its presence share one channel. NFTs function by enabling the artwork and its presence to circulate their own separate channels.[16] Accordingly, the two kinds of value can also circulate separate channels. The open channel transmits the exhibition value while the secured channel transmits the cult value. The secured channel, the blockchain, even has its own kind of ritual: proof of work. Ideologically, the proof of work ritual rather late capitalist: an all-too-familiar kind of competition (racing to find the hash), all nicely scaled up, globally distributed, and energy intensive. In response to mechanical potential destruction of presence, NFTs are not so much a reversal but rather a workaround. Indeed, as the Ethereum developers suggest in their response to the copy/paste problem, what happens in the open channel—the channel of mechanical reproduction—ceases to negate the NFT’s cult value. In their account, copy/paste ultimately provides more hype for the cult, and exhibition value ultimately enhances the cult value.

Forensic Proof of Work

So far it has been shown that in the case of NFT art, the object’s presence is loaded onto the blockchain through proof of work. This process entails the competitive, and rather ritualistic, solving of cryptographic hash problems—the search for a hash number that satisfies the system constraints. Once this work is complete and validated by the miners in the system, the latest block is successfully mined. The present state of affairs is then appended to the object’s worldline. In the case of traditional (here meaning analog and singular) artwork, access to the object’s presence occurs analogously, and tracing the parallel features of both processes helps explain the art market appeal of NFTs and NFTs’ ability to circulate the market like art of older, analog kinds.

In his account of what he calls the “conjectural paradigm” of the human sciences, Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg documents procedures of art authentication emergent in the late 19th century.[17] Ginzburg cites the 1874-1876 writings of Giovanni Morelli as introductive of the accepted approach in use in some ways even today. Previously, art historians occupied themselves with “the most conspicuous characteristics of the painting,” explains Ginzburg: “eyes raised towards the heavens in the figures of Perugino, Leonardo’s smiles, and so on” (97). In Morelli’s view, such an approach was ill-suited for sorting the growing mass of paintings in European museums. The problem was one of art historical knowledge: as more copies appeared and the originals themselves deteriorated, knowledge of the paintings lost certainty. Hence the need for a more reliable method for attributing and certifying artworks. Morelli proposed the following: refrain from studying a painting’s most important or conspicuous features—that is, those presumably receiving the most conscious attention from the artist, and as a result, the most attention from those making copies. Instead, connoisseurs should study “the most trivial details that would have been influenced least by the mannerisms of the artist’s school: earlobes, fingernails, shapes of fingers, and of toes” (97). In other words, examine the elements afforded the least conscious attention by the artist. In their inadvertent origins, such elements were the most authentic—closest to the innermost, and most difficult to emulate, aspect of the artist’s skill.[18]

Ginzburg describes Morelli’s approach as forensic in nature. He cites art historian Edgar Wind’s impression of Morelli’s journals: “careful records of the characteristic trifles by which an artist gives himself away, as a criminal might be spotted by a fingerprint” (98). He also compares Morelli’s conjectural connoisseur with the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes. In sum, the Morellian method is a procedure for identifying and certifying an artwork’s origins—for accessing its presence—based on the forensic analysis of clues embedded in its surface. Morelli’s clues were limited to visible traces of the artist’s gestures and accessible to the connoisseur’s unaided eye.[19] Since then, the range of clues has expanded with further technological augmentations to the connoisseur’s senses. Today, artistic attribution additionally relies on chemical analyses, X-ray filmography, and magnetic imaging. Benjamin himself recognizes the role played by chemical analysis in revealing “traces,” as he writes, of an artwork’s presence in the physical object (220). These more recent modes of analysis maintain the general forensic approach of the Morellian method; that said, the addition of forensic technologies invites new specialists to join in the connoisseur’s search for clues.[20]

NFTs are consonant with the Morellian method on two fronts. First is the problem each method is designed to address. Recall how Ethereum developers problematize digital objects’ absence of the “scarcity, uniqueness, and proof of ownership” that are, at least in their market-informed view, virtuous qualities of physical objects. In their view, copy/pasters exploit the affordances of digital media to replicate and reroute the circulation of digital artworks at will. Likewise, the students and forgers in Ginzburg’s account create copies that may accidentally (or intentionally) enter museum collections, similarly disrupting museum building and art historical scholarship. In both cases, access to the artwork’s presence is threatened by reproduction. In light of Shannon’s secrecy system, the copy/paster, student, and forger all resemble the enemy seeking to intercept the message. Following Michel Serres, all of these agents in turn relate to their respective networks as parasites.[21] Serres describes how parasites like these draw resources (here, presence-as-information) from the network, but, crucially, the parasite’s position in the system itself configures the system’s overall structure.

Both systems’ responses to their parasites brings us to the second site of consonance between NFTs and traditional art attribution. Like Morelli’s connoisseur/detective, NFTs access the artwork’s hidden presence using clues; they, too, employ forensic techniques. Recall how for NFTs, certain prized qualities of physical objects—scarcity, uniqueness, and proof of ownership—are reproduced virtually using proof of work. The “work” to prove here is the work of guessing. Mining involves guessing (and guessing and guessing) for the clue that solves the cryptographic hash problem. Here, access to the object’s presence is once again forensic. Conversely, the Morellian method is itself a kind of proof of work protocol—one that precedes the protocol introduced by Nakamoto in 2009 by over two centuries. Previously, the “Sherlock Holmes” of this process was the connoisseur (and more recently, the technician), and the clues resided in the physical object. In blockchain mining, Sherlock Holmes is automated by a mass of computational miners in server farms scattered across the globe. Here, the clues pertain to the metadata—the information fed into the hash function to produce a hash number. The structure is consistent across both cases. And ultimately, the parasite survives in both cases. The forgers continue forging and the copy/pasters continue copy/pasting. But the presence is rerouted, circumventing the parasite through new, forensic channels.

Conclusion

This paper has tracked precursors to NFTs’ technical features and cultural capacities in long extant systems and procedures of cryptography and connoisseurship. It demonstrates how NFTs use blockchain to create a two-channel system similar in structure and purpose to Shannon’s secrecy system. This system enables a digital file to circulate independently from its metadata. The metadata itself, now contained on a blockchain and secured from unauthorized alteration, carries the digital artwork’s presence. In effect, NFTs circumvent the effects of mechanical reproduction described by Benjamin. The artwork’s cult value is no longer replaced by its exhibition value; rather, the two values coexist, only on different channels, and reinforce one another.

Now contained on the technically novel blockchain, the presence of the artwork is maintained and accessed through forensic methods similar to those long employed in traditional forms of art authentication. Both the connoisseur’s Morellian method and the miner’s proof of work protocol entail a conjectural hunt for clues that, when found, open a channel to the artwork’s presence. Though seemingly novel as a technological medium, NFTs employ long extant concepts and procedures that singularize and valorize art. Presence and authentication, though still forensically accessed, are now globally distributed and algorithmically managed. They ultimately animate NFTs as cultural technologies, giving their databases, calculations, and connections meaning and relevance in a social system. They enable the production and sale of artworks like Beeple’s Everydays alongside some of our society’s most valued objects.

[1] Bryan Pfaffenberger, “Fetishised Objects and Humanised Nature: Towards an Anthropology of Technology,” Man 23, no. 2 (June 1988): 236.

[2] Alfred Gell, “The Technology of Enchantment and the Enchantment of Technology,” in The Art of Anthropology: Essays and Diagrams, repr, London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology 67 (Oxford: Berg, 1999), 159–86.

[3] This account is a rather detailed one for a non-technical audience, but this level of detail is needed for the analysis that follows.

[4] Haber, S. & Stornetta, W.S. (1999). How to time- stamp a digital document. In A. Menezes & S.A. Vanstone (Eds.), Proceedings of the 10th annual International Cryptography Conference on Advances in Cryptography (pp. 437-455). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.; Haber, S. & Stornetta, W.S. (1999). How to time-stamp a digital document. Journal of Cryptology, 3(2), 99–111.

[5] Nakamoto, S. (2009). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Retrieved from https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf. For more on Nakamoto and the early history of blockchain, see DuPont, Quinn. 2019. Cryptocurrencies and Blockchains. Medford, MA: Polity.

[6]https://ethereum.org/en/nft/

[7] The cryptocurrency corresponds to the blockchain in use. Miners on the bitcoin network receive bitcoin whereas miners on the Ethereum network receive Ethereum’s cryptocurrency called Ether. The cryptocurrencies can be sold for fiat currencies like USD if desired.

[8] For simplicity, this paper leaves out some logistical details like how the miners are linked into a system, how to connect to the system as a user, where the money for the reward comes from, etc. A good source for further detail is DuPont, Quinn. 2019. Cryptocurrencies and Blockchains. Digital Media and Society. Medford, MA: Polity.

[9] For discussions of the role of “trust” in blockchain systems, see Dodd, Nigel. 2018. “The Social Life of Bitcoin.” Theory, Culture & Society 35 (3): 35–56.

[10] This amounts to a double virtuality. First is the virtuality of the digital object itself—grounded in code but, at least in the case of an image, projected visually. Second is the virtuality of the metadata contained by the NFT.

[11] As mentioned in the introduction, this system comes with a whole series of vulnerabilities which are important for consideration but, again, are not in the scope of this paper. Dan Olson provides an extensive account of such vulnerabilities, in addition to more critiques of the NFT market in a 2022 video on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQ_xWvX1n9g).

[12] Shannon, Claude E. “Communication theory of secrecy systems.” The Bell system technical journal 28, no. 4 (1949): 656-715.

[13] M. Serres, The Parasite, (University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

[14] Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”

[15] As physical artworks increasingly circulate as speculative assets, they are often stored in warehouses called freeports, which are located in tax havens and allow the owners to shield the artwork from exposure to the both the environment and the tax collector. In line with Benjamin, the cult value remains regardless. Perhaps the “ritual” such art-as-assets serve in is the art auction (See Baudrillard, Jean. 1972. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign.)

[16] Indeed, this points to a gap in Benjamin’s account. Even when he was writing, a kind of second channel for presence existed: separate, detachable provenance documentation.

[17] C. Ginzburg, Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013).

[18] Indeed, the goal of the connoisseur, the user of the Morellian method, is connaître: to know, as if it were a person, the artwork (or the artist behind the artwork).

[19] Alfred Gell similarly locates the agency of artworks in their indexicality. Gell and Morelli’s both locate the essence of a work of art in the causal relation between artist and artwork. Gell’s account of artistic agency moves in one direction: from artist to viewer via artwork. Morelli’s account moves in the opposite: from viewer to artist via artwork. Much like a hash function, movement down the chain of causality, from input to output, is trivial, but movement in the opposite direction takes work in the form of conjecture. In both cases the artwork mediates the relation between artist and viewer. (Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory.)

[20] Unsurprisingly, researchers have been exploring approaches using artificial intelligence authenticate art. Approaches currently in use still follow a Morellian method, the goal still being to find clues inaccessible to the connoisseur’s naked eye (https://news.artnet.com/art-world/ai-research-changing-attributions-2057023)

[21] Serres, The Parasite.